In 1054 AD, an event known as the Great Schism, or the Schism of 1054, significantly marked Christian history. This event, referred to as the East-West Schism, led to a profound division within the Christian Church. Characterized by mutual excommunications, it irreversibly separated the Church into two branches: the Western Catholic and the Eastern Orthodox Churches. Stemming from a complex web of theological, political, and cultural differences, the schism has exerted a lasting influence on the Christian world and continues to be a pivotal moment in the histories of both Churches.

Historical Context and Background

Understanding the East-West Schism requires delving into the historical context preceding 1054 AD. The Roman Empire, once a unified entity under a single emperor, had gradually split into two distinct parts: the Western Roman Empire, with Rome as its capital, and the Eastern Roman Empire, also known as the Byzantine Empire, with Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul) as its seat of power.

This division was not merely political but also had profound religious and cultural implications. The Western Roman Empire, where Latin was the dominant language, saw the rise of the Roman Catholic Church under the Papacy. In contrast, the Eastern Roman Empire, predominantly Greek-speaking, was the cradle of the Eastern Orthodox Church, centered in Constantinople.

The theological rift between the two Churches had been widening over centuries. Key doctrinal disputes included the Filioque clause – an addition to the Nicene Creed concerning the Holy Spirit’s procession – and disagreements over papal authority. While the Pope in Rome claimed supremacy over all Christian bishops, the Eastern Church maintained a model of conciliarity, asserting the collective authority of bishops.

Cultural and linguistic differences further exacerbated these theological disagreements. The Western Church’s use of Latin in liturgy and doctrinal formulations often clashed with the Eastern Church’s preference for Greek, leading to misunderstandings and misinterpretations of key theological concepts.

Additionally, political tensions between the Byzantine Empire and various Western powers, including the Holy Roman Empire, created an atmosphere of distrust and rivalry that permeated ecclesiastical relations. These factors, combined with occasional conflicts over jurisdiction and church governance, set the stage for the eventual schism.

The mutual excommunications of 1054, although not the sole cause, marked the culmination of centuries of growing estrangement between the two branches of Christianity. This pivotal moment in 1054 AD, the East-West Schism, reshaped the religious and cultural landscape of Europe and the Christian world, forging separate paths that continue to diverge to this day.

Theological Disputes and Doctrinal Divergences

The East-West Schism’s roots can be traced to deep theological disputes that were simmering for centuries. Central to these disagreements was the Filioque controversy. The original Nicene Creed, a statement of faith adopted by both Eastern and Western Churches, proclaimed that the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father. However, the Western Church, without consulting the East, added the Latin term ‘Filioque’ (meaning ‘and the Son’) to the Creed, asserting that the Holy Spirit proceeds from both the Father and the Son. This unilateral alteration was vehemently opposed by the Eastern Church, who viewed it as a doctrinal overreach and a breach of ecclesiastical protocol.

Another major point of contention was the role and authority of the Pope. The Western Church, particularly under the leadership of Pope Leo IX, asserted the doctrine of Papal Supremacy, which held that the Bishop of Rome had authority over all other bishops in Christendom. The Eastern Church, valuing a more conciliar approach to governance, vehemently disputed this claim. They argued for a model of Pentarchy, where the five major episcopal sees (Rome, Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem) held equal authority.

These theological and doctrinal differences were not simply matters of church governance or creed formulations. They were deeply embedded in the cultural and philosophical outlooks of the Eastern and Western Churches. The Greek-influenced Eastern Church placed a higher emphasis on mystical theology and the direct experience of the divine, while the Latin-speaking Western Church focused more on legalistic and scholastic approaches to theology.

Political and Cultural Influences

While theological disputes were central to the schism, political and cultural factors played an equally crucial role. The decline of the Western Roman Empire and the rise of the Byzantine Empire created a power vacuum in the West, which the Papacy sought to fill. This shift in power dynamics led to increasing tensions between the Pope in Rome and the Byzantine Emperor in Constantinople.

Cultural differences also contributed significantly to the divide. The East, with its Greek heritage, and the West, grounded in Latin traditions, developed distinct liturgical practices, church laws, and approaches to religious art. For instance, the Eastern Church’s use of icons was at times viewed with suspicion by the Western Church, which had different aesthetic sensibilities.

The mutual distrust was further fueled by the Western Church’s alignment with the Frankish Kingdom and the Holy Roman Empire. These alliances were often seen by the Byzantine Empire as encroachments on their territory and influence, particularly in regions like Southern Italy and the Balkans where the Eastern Orthodox Church had established strongholds.

These complex interplays of theology, politics, and culture set the stage for the events of 1054 AD, when centuries of accumulated differences finally culminated in the formal division of the Christian Church into the Eastern Orthodox and Western Catholic branches.

The Climax of the Schism – The Events of 1054

The schism reached its apex in 1054, a year marked by a series of dramatic and consequential events. The immediate trigger was a dispute over the appointment of the Patriarch of Constantinople. The Western Church’s insistence on recognizing a candidate favorable to Rome was met with resistance from the Eastern Church. This conflict escalated when Pope Leo IX sent a delegation, led by Cardinal Humbert, to Constantinople. The delegation was tasked with negotiating but instead further inflamed tensions.

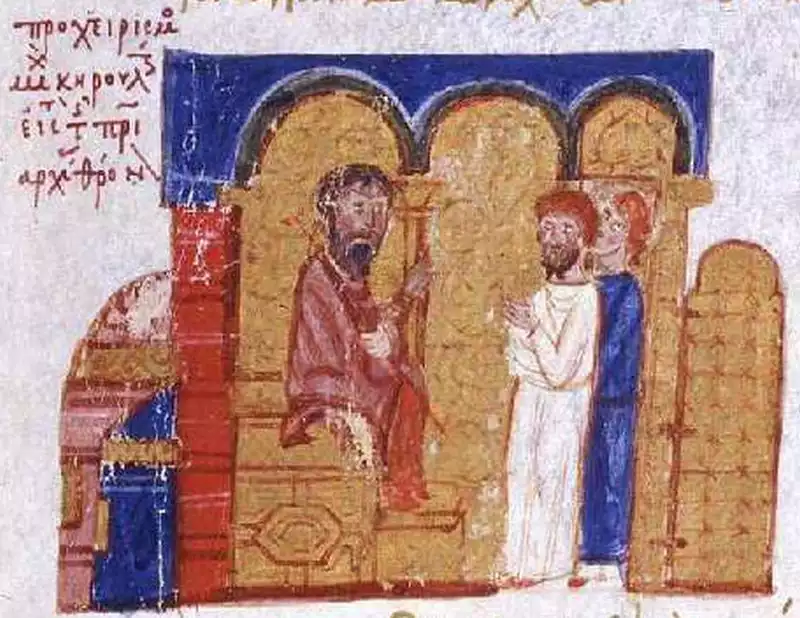

Upon arrival in Constantinople, Cardinal Humbert found himself in direct conflict with Patriarch Michael Cerularius. The negotiations deteriorated rapidly, marred by cultural misunderstandings and theological disagreements. The breaking point came when Cardinal Humbert, frustrated with the Patriarch’s refusal to recognize Papal authority, laid a bull of excommunication against Cerularius on the altar of the Hagia Sophia. In a dramatic response, Patriarch Cerularius convened a synod and excommunicated the papal legates.

These mutual excommunications, though not immediately severing all ties between the Churches, symbolized the profound rift that had developed. They were the culmination of centuries of accumulated grievances and misunderstandings, marking a point of no return in the relationship between the Eastern and Western Churches.

The Aftermath and Legacy of the Schism

The aftermath of the schism had far-reaching consequences for both the Eastern and Western Churches. In the immediate years following 1054, there were attempts at reconciliation, but these efforts were hindered by entrenched positions and ongoing political conflicts. The Crusades, particularly the Fourth Crusade and the sack of Constantinople in 1204, further deepened the animosity between the two Churches.

The schism had a lasting impact on the religious, cultural, and political landscape of Europe. It solidified the division of Christianity into Eastern Orthodoxy and Western Catholicism, each developing its own distinct theological traditions, liturgical practices, and ecclesiastical structures. This division also influenced the political alliances and conflicts in Europe for centuries to come.

Moreover, the schism had profound cultural implications. It contributed to the divergent development of Eastern and Western Europe, not only in religious matters but also in art, philosophy, and social structures. The separation limited the exchange of ideas and cultural interaction between the two regions, leading to distinct paths of development.

The legacy of the 1054 East-West Schism is still evident today. While there have been significant efforts towards ecumenical dialogue and reconciliation, the divide remains a central feature of the Christian world, shaping the religious and cultural identity of millions of believers.

Modern Implications and Ecumenical Efforts

The ripple effects of the 1054 East-West Schism extend into the modern era, influencing the dynamics of contemporary Christian theology and inter-church relations. The 21st century has witnessed renewed efforts towards reconciliation and dialogue between the Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic Churches. These endeavors are characterized by a mutual recognition of shared heritage and a commitment to overcoming doctrinal differences through understanding and respect.

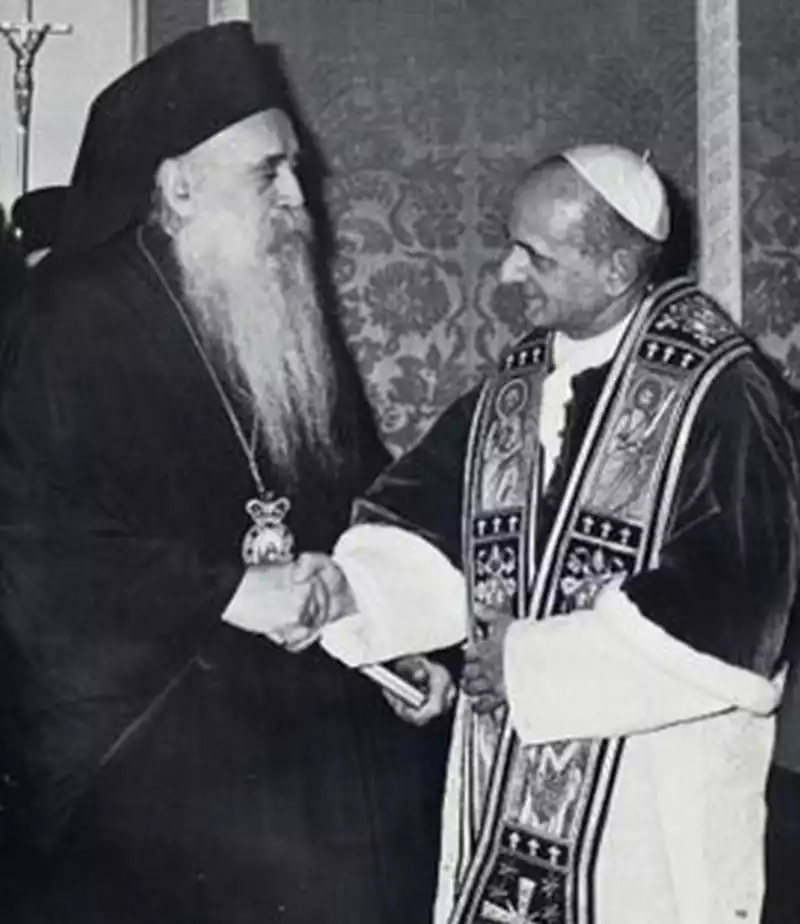

Pope John Paul II and subsequent Popes have made significant strides in fostering dialogue with the Eastern Orthodox Church. Joint declarations and theological discussions have aimed at resolving long-standing disputes, particularly focusing on the nature of Papal primacy and the Filioque controversy. These dialogues have been accompanied by symbolic gestures, such as the mutual lifting of the 1054 excommunications in 1965 by Pope Paul VI and Patriarch Athenagoras of Constantinople.

Eastern Orthodox Churches, under the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople, have reciprocated these efforts, engaging in numerous ecumenical meetings and joint initiatives. The goal of these dialogues is not to seek a return to administrative unity but rather to foster a unity of faith and mutual understanding, respecting the distinctive traditions and theological expressions of each Church.

Despite these efforts, significant challenges remain. Internal disagreements within both the Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic Churches, cultural differences, and historical grievances continue to impede the path towards full reconciliation. However, the commitment to dialogue and the recognition of a common Christian heritage offer hope for a future where the divisions of the past can be healed.

The East-West Schism of 1054 AD remains one of the most pivotal events in Christian history. Its impact on the religious, cultural, and political landscapes of Europe and beyond is undeniable. While the schism entrenched divisions that have lasted for centuries, contemporary efforts towards dialogue and understanding signify a desire to bridge the gap that has long separated the Eastern and Western branches of Christianity. The path to reconciliation is complex and fraught with challenges, but the continued pursuit of unity reflects the enduring spirit of the Christian faith.

References

- “Academic Accelerator | Encyclopedia – East-West Schism.” Academic Accelerator, Accessed 01 January 2024.

- “Ancient Origins | The Great Schism.” Ancient Origins, Accessed 01 January 2024.

- Chadwick, Henry. “East and West: The Making of a Rift in the Church.” Oxford University Press, 2005.

- “East and West Cultural Dissonance and the Great Schism of 1054.” Academia.edu, Accessed 01 January 2024.

- Hussey, J.M. “The Orthodox Church in the Byzantine Empire.” Oxford University Press, 1986.

- Meyendorff, John. “Catholicity and the Church.” St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1997.

- “National Geographic Education | The Great Schism.” National Geographic Education, Accessed 01 January 2024.

- Obolensky, Dimitri. “The Byzantine Commonwealth: Eastern Europe, 500-1453.” Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1971.

- Runciman, Steven. “The Eastern Schism: A Study of the Papacy and the Eastern Churches During the XIth and XIIth Centuries.” Cambridge University Press, 1955.

- Ware, Timothy. “The Orthodox Church: An Introduction to its History, Doctrine, and Spiritual Culture.” Penguin Books, 1997.