The year 893 AD marked a pivotal moment in Christian history, witnessing the resolution of the Photian Schism, a decades-long rift between the Eastern and Western branches of the Church. This schism, centered around the controversial figure of Photios, threatened to fracture Christian unity and had simmered for over a decade. However, the Council of Constantinople convened that year successfully healed the wounds and restored communion between the two patriarchates.

Roots of the Schism and the Rise of Photios

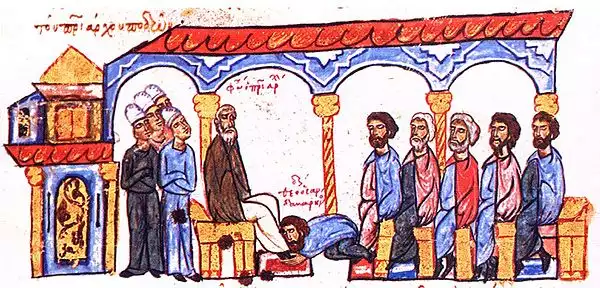

The seeds of the Photian Schism were sown in 858 AD with the deposition of Ignatios, the Patriarch of Constantinople, by Emperor Michael III. In his place, the erudite and ambitious Photios, a layman, was consecrated as patriarch. This unorthodox elevation, coupled with Photios’ close ties to the emperor, drew immediate condemnation from Pope Nicholas I in Rome. The ensuing years saw a flurry of accusations and counter-accusations, with both sides questioning the legitimacy of the other’s patriarch.

Photios, a skilled diplomat and theologian, defended his position with vigor. He authored numerous treatises justifying his consecration and challenged papal authority in the East. The dispute escalated further when Photios condemned the addition of the filioque clause to the Nicene Creed, a theological divergence that had long simmered between Rome and Constantinople.

By 886 AD, the schism had reached an impasse. Neither side was willing to budge, and communication between the two patriarchates had ceased. The Christian world stood on the brink of a major division.

A Delicate Dance of Diplomacy and Dogma

The Council of Constantinople in 893 convened under the shadow of the schism, its task monumental: to bridge the chasm between the Eastern and Western churches. Emperor Leo VI, Photios’ successor, played a crucial role in orchestrating the council. Recognizing the need for compromise, he invited papal legates and ensured due process for both sides.

Debates were lively, with complex theological and political issues intricately interwoven. The legates challenged Photios’ initial consecration, while Photios defended his position with characteristic eloquence. Yet, amidst the disagreements, a spirit of reconciliation gradually emerged. Both sides acknowledged the validity of the other’s sacraments and agreed to recognize Ignatios’ initial deposition as invalid.

Crucially, the council sidestepped the contentious filioque issue, opting for a pragmatic silence. This averted a head-on clash on a major theological point and paved the way for a fragile unity. Recognizing the need for compromise, Pope Stephen VI ultimately approved the council’s decisions, formally ending the schism and restoring communion between the Eastern and Western churches.

The Council of Constantinople in 893 stands as a testament to the power of diplomacy and compromise in resolving religious conflict. Although the schism left its scars, the council’s success in restoring communion prevented a potentially catastrophic division within Christianity. While theological differences remained, the council established a foundation for future dialogue and cooperation between the Eastern and Western branches.

References

Haldon, John.* Byzantium: A History. Pearson Education, 2000.

McManners, John. The Oxford History of Christianity. Oxford University Press, 2002.

Norwich, John Julius. Byzantium: The Decline and Fall. Viking, 1995.

Teitelbaum, Joshua.* Medieval Church. Routledge, 2014.