The Act of Toleration, passed by Parliament in May 1689, marked a turning point for religious freedom in England. Though far from full religious liberty, the Act granted significant new rights to certain Protestant nonconformists who dissented from the Church of England.

The Long Road to the Act of Toleration

The Act of Toleration of 1689, which granted limited religious freedom to certain Protestant nonconformists in England, was the culmination of a long struggle by dissenters against state persecution.

Groups such as Puritans, Baptists, and Quakers had faced decades of discrimination and restrictions under English law. They were barred from holding public office, and their right to worship was severely curtailed. Puritans fled persecution under the restoration of the monarchy in 1660. Quakers like George Fox were regularly imprisoned for unauthorized preaching.

Religious tensions finally exploded into civil war in the 1640s, pitting Puritan Roundheads against Anglican Cavaliers. After victory for the Roundheads and the interregnum rule of Oliver Cromwell, the Restoration saw reprisals against nonconformists. The Clarendon Code imposed stiff penalties for unauthorized worship.

By the 1680s, dissenters had organized under leaders like William Penn into a more unified political bloc. A bill for religious tolerance failed to pass under Charles II in 1685. But when William and Mary took the throne in the Glorious Revolution of 1688, nonconformists saw a new opportunity to argue for liberty of conscience with the monarch.

The Act of Toleration fulfilled some of these hopes, while dashing others. Protestant dissenters celebrated their new freedoms of public worship and assembly after years of repression. But the exclusions remained disappointing, as Quakers, Catholics and other minorities still faced restrictions. The fight for full religious liberty would take many more decades.

The Act of Toleration – Who It Covered and Who It Left Out

The Act of Toleration was a compromise piece of legislation. While granting significant new freedoms to Protestant nonconformists who dissented from the Church of England, the Act only applied to certain denominations that affirmed basic Christian doctrine. Many minorities were left out in the cold.

Puritans, Baptists, Congregationalists and other nonconformist sects that had fought long years for religious liberty were now allowed their own preachers and places of worship, so long as those places were registered and the doors were left unlocked during services. For these permitted sects, celebrations erupted across England in the weeks after the Act’s passage.

Yet glaring exclusions remained. Quakers, Unitarians, and other groups still faced restrictions for failing religious tests on the doctrines of the Trinity and the Bible. England’s Jewish population also saw no relief, though their numbers were quite small.

Perhaps most controversially, Catholic worship continued its illegal status under the Act. Catholics were seen by many Protestant Englishmen as representing the old specter of foreign despotism and superstition linked to Bloody Mary’s reign. Anti-Papist sentiments died hard. Catholics in England would not achieve full religious emancipation until 1829.

So while the Act of Toleration helped inaugurate a new era of religious diversity in England, it fell short of the claims it made to “liberty of conscience.” Many dissenters would continue lobbying for fewer restrictions and fewer state-sponsored religious tests over the coming decades. Yet as the renowned English poet John Milton had written during Cromwell’s rule, true religious liberty ultimately depended “on the individual’s spiritual and intellectual energies to perceive the divine.” And for some, even the Act’s basic freedoms gave a taste of such individual spiritual liberty.

The Act of Toleration of 1689 represented a significant milestone on the path to religious liberty, though it provided only limited emancipation. Dissenting Protestants celebrated their new freedoms while Catholics and other minorities were left disappointed. Yet the Act shattered past uniformity, allowing pockets of diversity to sprout. It inaugurated a gradual religious opening-up that continued over subsequent decades. Full liberty of conscience awaited future political victories, but the Act gave nonconformists their first taste since the Restoration—and for some Baptists leaving prison, their first ever.

References

Gibson, William. Church, State and Society, 1760-1850. Macmillan Education UK, 1994.

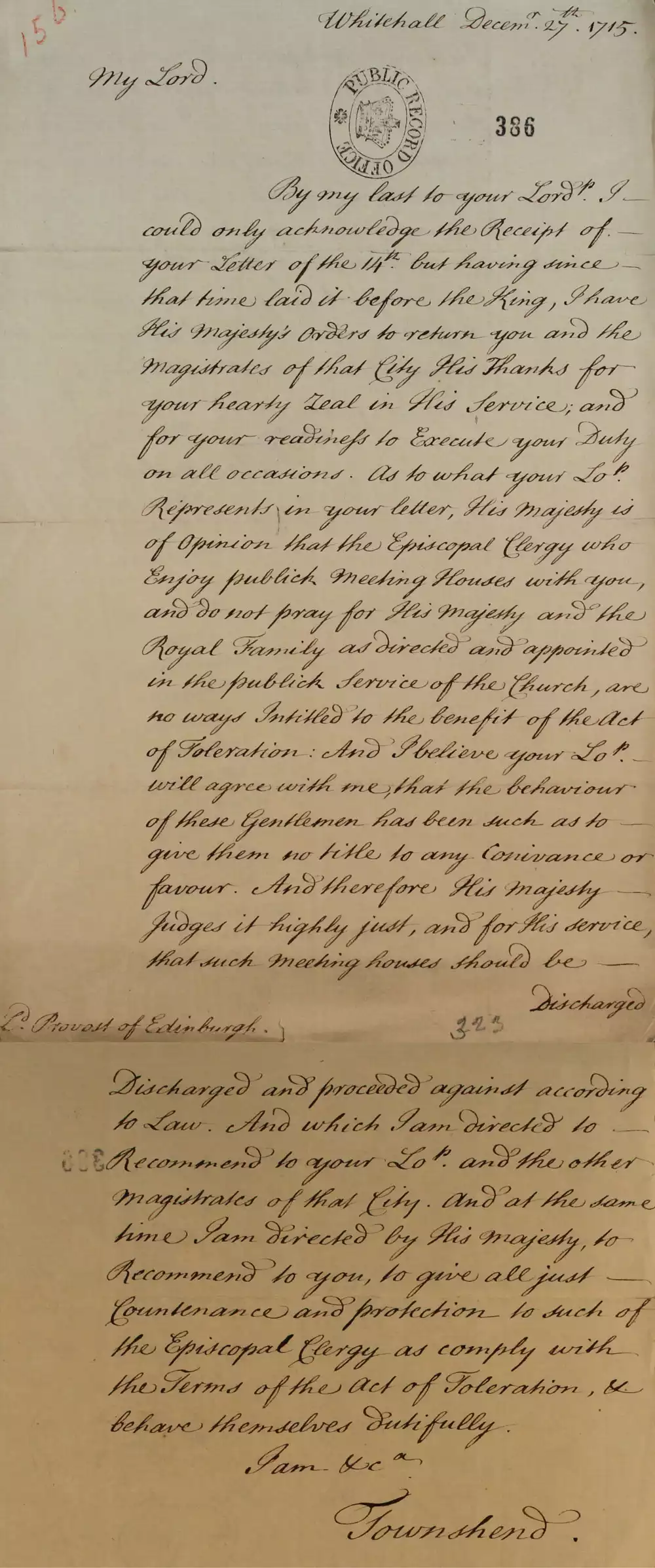

National Archives. (2023). A letter from Secretary Townshend to the Provost of Edinburgh [the chief magistrate] reminding him that legal action will be taken against churchmen who do not pray for the royal family in their services and they will not be to able practice their faith freely as provided by the Toleration Act*, (SP 54/10/156).

Spurr, John. “The Church of England, Comprehension and the Toleration Act of 1689.” The English Historical Review 104, no. 413 (1989): 927-46.

Spellman, W. M. The Latitudinarians and the Church of England, 1660-1700. University of Georgia Press, 1993.