The Genesis of Christianity – A Historical Overview

Christianity, a monotheistic religion centered on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ, emerged in the first century AD within the context of Jewish tradition. The etymology of the term ‘Christianity’ stems from the Greek ‘Christianos’, meaning ‘follower of Christ’, a title first used in Antioch (Acts 11:26).

The life and ministry of Jesus Christ, central to Christian belief, is chronicled in the New Testament of the Bible. The Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John offer accounts of His teachings, miracles, crucifixion, and resurrection, laying the foundation for Christian doctrine. The apostolic era, following Christ’s ascension, marked significant growth and doctrinal development, as depicted in the Acts of the Apostles and the Epistles.

The early Christian community faced persecution under Roman rule, notably during the reigns of emperors Nero and Diocletian. Despite this, Christianity continued to spread, driven by missionary work and the theological writings of early Church Fathers like Augustine and Origen.

The Edict of Milan in 313 AD, issued by Emperor Constantine, granted religious tolerance across the Roman Empire, significantly altering Christianity’s status. The subsequent Council of Nicaea in 325 AD marked a pivotal moment in defining orthodox Christian doctrine, particularly concerning the nature of Christ and His relationship to God the Father.

Christianity’s spread beyond the boundaries of the Roman Empire laid the groundwork for its evolution into various forms. The Great Schism of 1054 AD resulted in a permanent division between the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Roman Catholic Church, each with distinct theological and liturgical traditions.

The Establishment of Christianity as a State Religion and Its Expansion

The transition from Christianity being a persecuted faith to its establishment as a state religion under the Roman Empire marks a significant chapter in its history.

The pivotal moment for Christianity came with Emperor Constantine’s conversion in the early 4th century. His subsequent policies, including the Edict of Milan in 313 AD, not only ended persecution but also patronized Christianity, leading to its rapid expansion within the Roman Empire. The Council of Nicaea in 325 AD, convened by Constantine, was a landmark in establishing unified Christian doctrine, notably the Nicene Creed, which remains a cornerstone of Christian faith.

Following Constantine, Emperor Theodosius I declared Christianity as the state religion of the Roman Empire in 380 AD, through the Edict of Thessalonica. This decree was a turning point, signaling the end of pagan practices within the empire and establishing Christianity as the dominant religious force. This integration of church and state played a crucial role in shaping the religious, social, and political landscape of Europe.

The fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century did not halt the spread of Christianity. Instead, it found new avenues for expansion, notably through the missionary endeavors of figures like St. Augustine of Canterbury in England and St. Patrick in Ireland. These missions not only spread Christianity but also helped to preserve literary and cultural traditions during the Middle Ages.

The rise of monasticism, with its emphasis on asceticism and learning, contributed significantly to Christianity’s spread and institutional strength. Monasteries became centers of education, culture, and spiritual life, playing a pivotal role in the Christianization of Europe. St. Benedict’s establishment of the Benedictine rule in the 6th century provided a model for monastic life that shaped Western monasticism.

Christianity’s expansion was not limited to Europe. The Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire saw the spread of Christianity into Eastern Europe, including the conversion of the Bulgarians and the Russians. These expansions brought about the creation of distinct Christian traditions, influenced by local cultures and languages.

In summary, the establishment of Christianity as a state religion under the Roman Empire and its expansion throughout Europe and beyond during the Middle Ages was a complex process involving political, cultural, and theological elements. This period laid the foundations for the diverse expressions of Christianity that would emerge in the following centuries.

The Great Schism and the Emergence of Eastern Orthodoxy

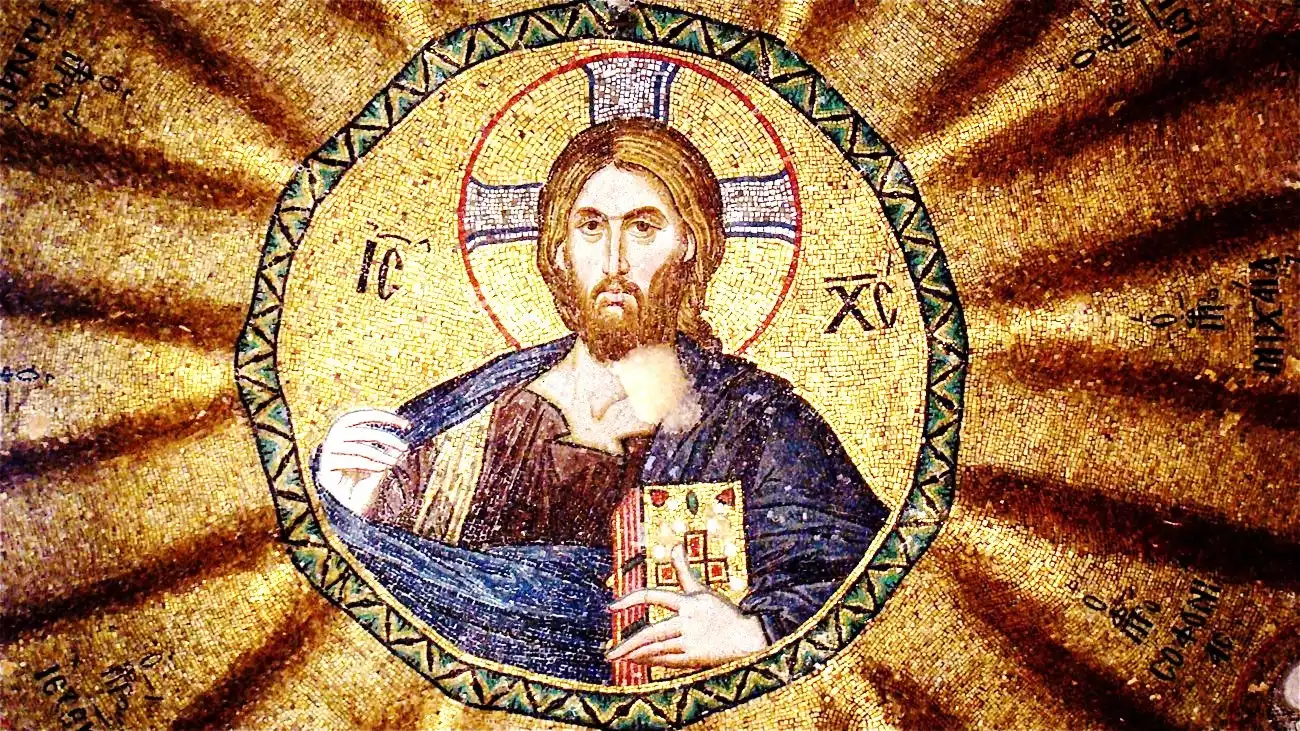

The Great Schism of 1054 AD, a pivotal event in Christian history, led to the definitive split between the Western Church, centered in Rome, and the Eastern Church, centered in Constantinople.

The roots of the Schism lay in long-standing theological, political, and cultural differences between the Eastern and Western parts of the Christian world. Key theological disputes included the Filioque clause in the Nicene Creed and disagreements over the nature of the Holy Trinity. The Filioque controversy, concerning the procession of the Holy Spirit, became a significant point of contention.

Cultural and linguistic differences further deepened the divide, with the Western Church using Latin and the Eastern Church using Greek. These differences led to varied theological interpretations and ecclesiastical practices. The mutual excommunications in 1054 by Pope Leo IX and Patriarch Michael Cerularius symbolized the culmination of these long-standing tensions.

Eastern Orthodoxy, following the Schism, developed a distinct identity, characterized by its adherence to the original decisions of the first seven Ecumenical Councils and a strong emphasis on liturgical tradition. The Orthodox Church also maintained a decentralized ecclesiastical structure, with national churches enjoying a significant degree of autonomy while remaining in communion with each other.

The Roman Catholic Church – Centralization and Influence

Following the Great Schism, the Roman Catholic Church emerged as a powerful and centralized institution within Western Christianity.

Central to the Catholic Church’s structure is the papacy, with the Pope as the spiritual leader and ultimate authority. The concept of papal primacy, which asserts the Pope’s authority over all Christians, became a defining feature of the Catholic Church. This period saw influential popes like Gregory VII and Innocent III, who significantly shaped the church’s direction and its role in European politics.

The Catholic Church played a pivotal role in medieval society. It was not just a spiritual institution but also a significant political and economic force. The church’s influence extended into various aspects of life, including education, art, and science. Monastic orders like the Franciscans and Dominicans, founded in the 13th century, contributed to theological scholarship and the spread of Christian doctrine.

The 11th to the 13th centuries marked a period of reform within the Catholic Church. The investiture controversy, a conflict over the appointment of church officials, led to significant changes in church-state relations. The Lateran Councils, convened during this era, addressed issues of clerical discipline and corruption, aiming to reform the church from within.

Art and architecture flourished under the patronage of the Catholic Church, giving rise to Gothic cathedrals and masterpieces of Renaissance art. These creations not only demonstrated the church’s wealth and power but also served as expressions of faith and devotion.

Theological development was another crucial aspect of this period. Thomas Aquinas, a prominent theologian, synthesized Aristotelian philosophy with Christian doctrine, profoundly influencing Catholic theology.

However, the Church also faced challenges, notably the Avignon Papacy and the Western Schism, which eroded its authority and credibility. These events, coupled with growing calls for reform, set the stage for significant upheavals in the 16th century, leading to the Protestant Reformation.

In summary, the Roman Catholic Church, through its centralization and influence, profoundly shaped the religious, cultural, and political landscape of medieval and Renaissance Europe, laying the groundwork for future developments and challenges within Christianity.

The Modern Landscape of Christianity and Its Future Directions

In the modern era, Christianity continues to evolve, reflecting both its historical roots and contemporary challenges.

Christianity has become a truly global religion, with significant growth in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. This shift has introduced new cultural expressions of faith and different theological perspectives, enriching the Christian tradition. The rise of Pentecostalism and Evangelicalism represents a significant trend, emphasizing personal faith experience and missionary work.

The ecumenical movement, aiming to foster unity among Christian denominations, has gained momentum. The World Council of Churches, established in 1948, embodies this effort, bringing together various Protestant, Orthodox, and Anglican churches. Dialogue with the Roman Catholic Church, particularly since the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965), has been a notable development in this regard.

Contemporary Christianity faces numerous challenges, including secularization, ethical dilemmas posed by scientific advancements, and the need for interfaith dialogue in an increasingly pluralistic world. These issues prompt ongoing theological reflection and adaptation.

Looking ahead, Christianity’s future will likely be shaped by its ability to engage with a rapidly changing world while staying true to its core teachings. The interplay between tradition and innovation, centralization and diversity, will continue to define its path.

References

- Pelikan, Jaroslav. The Christian Tradition: A History of the Development of Doctrine. University of Chicago Press, 1971-1989.

- Ware, Kallistos. The Orthodox Church: An Introduction to its History, Doctrine, and Spiritual Culture. Wiley-Blackwell, 2012.

- Yale University Library Guide to Research in Religion (accessed December 11, 2023)

- Boston College Paper on Christianity (accessed December 12, 2023)